« How may those who since birth have only known walls with blind holes and desolate streets, understand the irresistible attraction of our “Mare nostrum” and the obsessive desire to return. »

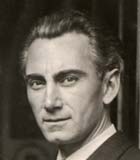

Henri Tomasi

Henri TOMASI was born in Marseilles on 17 August 1901 of Corsican parents. It was his father, Xavier Tomasi, an amateur flautist and pioneer folklorist (with the publication of the song collections Corsica and Chansons de Cyrnos) who decided his destiny as a musician. His Mediterranean roots were the distinctive trait of both the man and the work. Corsica, the ‘Island of Light’, passionate, wild, Marseilles, the port of dreams and gateway to Africa and the Far East, and Provence, imbued with “ancient pagan beauty”, were to leave indelible marks on him. The young Henri Tomasi entered his local conservatory where, in record time, he obtained First Prizes for theory, piano and harmony. A childhood of poverty – which left him with an inalienable sense of justice – forced him at the age of 15 to play the piano in some of the very first cinemas, though through his improvisations he revealed a gift for composition.

With a grant from the city of Marseilles, and aided by a benefactor, the lawyer Levy-Oulman, he pursued his studies at the Paris Conservatory where he was the pupil of Charles Silver (harmony), Georges Caussade (counterpoint and fugue), Paul Vidal (composition), Vincent d’Indy and Philippe Gaubert (orchestral conducting). In 1927 he won a Premier Second Grand Prix de Rome and a unanimous First Prize for conducting. He at once started a career as a conductor with the Concerts du Journal and also for one of France’s first radio stations, Radio-Colonial (1931). At the same time he showed himself to be a composer with three symphonic poems, Cyrnos (1929), written in the year of his marriage with the draughtswoman and painter Odette Camp, Tam-Tam (1931), and Vocero (1932). He became a member m 1932 of the contemporary music group TRITON, the Honorary Committee of which included Ravel, Roussel, Schmitt, Stravinsky, Bartok, Enesco, de Falla, Schönberg, and Richard Strauss. Having conducted the foremost French and European ensembles, and, from 1946 to 1952, having been principal conductor at the Operas of Monte-Carlo and of Vichy, he abandoned his conducting career in about 1956 on account of the deafness that darkened the whole of his latter years and in order to be able to devote himself totally to composition. On 13 January 1971, while completing an a cappella arrangement of his Chants populaires de l’Ile de Corse, he died in Paris, a city that had always been a place of exile for him.

His output – about 120 opus numbers – is as abundant and diverse in the operatic and stage genres as in the symphonic domain. It was crowned, in 1952, with the Grand Prix de la Musique Française (awarded by the French performing rights society SACEM), and by the Grand Prix Musical de la Ville de Paris in 1960. His works include a score of highly virtuoso concertos: for trumpet (1948), saxophone (1949), viola (1950), clarinet (1956), trombone (1956), violin (1962), flûte (1965), harp (1966), guitar (“dedicated to the memory of an assassinated poet, F.G. Lorca”, 1966). Tomasi’s love of the voice, dance, the theatre, as well as his quest for great texts, inspired him, at very different periods in his life (from sensual exaltation he turned to mystical searching, then to a humanist commitment: his “successive sincerities” as he called them) – to compose masterpieces, some of which are a forceful record of the twentieth century: Don Juan de Mañara (or Miguel Mañara, an opera based on the Mystère by O.V. de Lubicz-Milosz (1944) dedicated to his son Claude, from which the Fanfares liturgiques were taken), Requiem pour la Paix (1945), L’Atlantide (from Pierre Benoît, 1951), Triomphe de Jeanne (from Philippe Soupault, 1955), Le Silence de la Mer (from Vercors, 1959), La Chèvre de Monsieur Seguin (from A. Daudet, 1962), L’Éloge de la Folie (from Erasmus, 1965), Retour à Tipasa (from Albert Camus, 1966), the Symphonie du Tiers-Monde en hommage à Berlioz (from Aimé Césaire, 1967).

A “protean musician” according to Emile Vuillermoz, Henri Tomasi developed a language inseparable from Mediterranean civilization: sensorial, multi-coloured, a fabric of light and shade, vibrant with melodic warmth, extolling in turn the flesh and the spirit. As the musicologist Frédéric Ducros has written, “Tomasi was able to use the musical resources of his time while remaining independent of Systems, and inspiration, that key value denied by the decadents, goes hand in hand, in perpetual renewal, with an orchestral variety that makes him, after Ravel, one of the virtuosos of that science.”